A Choreomusical Analytic Approach to a Dance-Music Performance of “El choclo”

Introduction

In Chapter 15 of the Cambridge Companion to Tango (2024), I provided an in-depth choreomusical transcription and analysis of Gerardo Matos Rodríguez’s “La cumparsita,” exploring the rhythmic interactions that emerge between music and dance as performed by dancers Cecilia Narova and Juan Carlos Copes in an iconic scene from Carlos Saura’s film Tango. Here, I apply this choreomusical analytic approach to a performance of another well-known representative of the tango genre—Ángel Villoldo’s “El choclo”—showing how musicians and dancers engage with this famous piece in interesting ways. As with my analysis of “La cumparsita,” I will highlight both moments where dancers align their movement patterns with existing musical patterns to draw out specific elements from within the musical texture, as well as moments where dancers create new rhythmic patterns that are not supplied obviously by the music.

The Performance

The performance of “El choclo” features Eleonora Kalganova and Michael Nadtochi dancing to a recording by Héctor Varela’s Orquesta Típica at a milonga in New York City in 2015. Annotations beneath the video mark the contrasting and returning formal sections (A, B, and C) as they arrive in the music. Please enjoy this captivating three-minute performance in its entirety:

Dancing the Rhythm versus Dancing the Melody

In his book, Social Partner Dance: Body, Sound, and Space, David Kaminsky notes that tango dancers will “sometimes discuss making a choice between ‘dancing the rhythm’ and ‘dancing the melody’” (2020: 98-99). Let us reconsider two passages from Kalganova and Nadtochi’s performance that illustrate these two approaches to physical engagement with musical material.

In the first passage, taken from the B section, the dancers time their footwork patterns to musical pulse streams at differing rates. At the beginning of the excerpt, you can observe a physical representation of the quarter-note pulse layer of the music if you keep track of the pattern of kicks for each individual dancer. If you then shift your attention to the alternation of kicks between the two dancers, whose footwork patterns are offset from each other, you will see the faster-moving eighth-note pulse layer represented. In the second half of the excerpt, Kalganova steps in eighth notes while rotating her partner, who provides a backwards kick every half-note duration. Finally, near the end of the section, Kalganova times her leg flourishes and steps to the quick-moving sixteenth notes of the bandoneón. In these ways, the dancers add visually perceptible increasing physical momentum to the audibly perceptible increasing musical momentum as the musicians and dancers drive collectively to the cadential arrival of the section.

The second passage to rewatch is a return of the D-minor A section but with a slower-moving violin countermelody provided instead of the usual A-section melody. Here, you will see the dancers rotate together counterclockwise. Nadtochi’s backwards eighth-note steps facilitate Kalganova’s elegant, legato leg and foot flourishes, which effectively match the soaring and expansive violin melody. When the piano takes over as the music’s main melodic focus in the second half of the section, you will see Kalganova again match her quick-stepping flourishes to the piano’s sixteenth-note embellishments, while also marking some of the violin’s punctuating gestures. As the section draws to a close, Kalganova’s swiveling step pattern continues to match the piano’s rippling and now more extended series of sixteenth notes, carrying the couple to the far end of the dance floor.

Uncovering Patterns Using Choreomusical Transcription and Analysis

While I find the two previous examples of dance-music correspondence effective and engaging to observe, I am also interested in uncovering patterns that are not as immediately obvious on a first watch/listen. As a dance-music theorist, I look to discover deeper patterns by utilizing detailed choreomusical transcription and analysis. To illustrate some of the complex rhythmic interactions that emerge between music and dance through this analytic approach, I’ll first examine the A section of the music on its own in some detail, at both large- and small-scale structural levels. I will then present the dance notation system I have developed to show how dance patterns further enrich the performance by adding interesting rhythmic layers that both respond to musical structures and interact with them in some surprising ways.

A Musical Analysis of the A Section

The left side of the musical example below shows two small-scale rhythmic patterns that are characteristic of “El choclo” and of tango more broadly—the 3+1+2+2 habanera rhythm in the bass, and the repeated 1+2+1 síncopa rhythm which permeates much of the melody in this A section. If we examine the way melody and harmony are organized within each four-measure phrase unit, we notice some similar rhythmic patterns playing out on the larger scale as well. As shown with the yellow and orange boxes on the right side of the example, the harmonic chord changes divide each four-measure unit into a 3+1-measure pattern for the first three phrases. Simultaneously, as shown with blue boxes, the melody provides consistent two-measure motives, dividing each of the first three phrases into a 2+2 pattern. In other words, we might observe that the two halves of the habanera rhythm are found in these large-scale harmonic and melodic patterns—the 3+1 first half of the habanera in the chord changes, and the 2+2 second half in the melodic motives. In the final four-measure phrase, the rate of change begins to speed up both melodically and harmonically as we near the close of the section. While the chord changes now occur once per measure, the repeated melodic fragmentation that occurs in the middle of this last phrase creates a two-measure unit sandwiched between two one-measure units—that is, in this final phrase, the síncopa rhythm has emerged on this larger melodic scale as well.

And now, let us add a detailed account of dance patterns into this rhythmic mix in order to uncover, through transcription, how dance layers further contribute to and interact with these various musical layers.

A Tango Dance Notation System

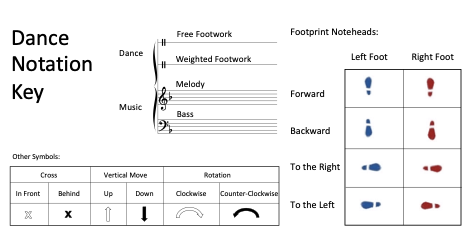

As shown in the example below, my tango dance notation adds two single-lined staves to a standard musical system—one line for weighted footwork like steps (where the dancer’s full weight is transferred onto that foot), and one line for free footwork (where the dancer provides embellishments such as kicks, toe taps, and so on). I then use standard musical durations such as quarter notes and eighth notes to keep track of when, in relation to the music, these dance steps and embellishments occur. The noteheads of the dance durations, however, are footprints that carry their own additional information; the colour (blue or red) indicates with which foot the dancer is stepping or embellishing, and the orientation indicates in what direction that step or embellishment is traveling. Finally, additional symbols added above or below footprint noteheads indicate steps that involve one foot crossing in front or behind the other foot, as well as steps that involve or facilitate a vertical movement or a rotation of the dancer’s body, either alone or in combination with their partner. Please note that all of the directional information is presented from the perspective of the individual dancer rather than the observer, and that for the purposes of clarity and simplicity, I have chosen to transcribe only Kalganova’s footwork, although Nadtochi is often doing analogous or complementary patterns at the same time.

A Brief Choreomusical Analysis

The video clip below once again returns to the performance we have already seen, providing a detailed transcription of the opening four measures as a brief example of this notational system in action. Here is what you will see when you rewatch this passage of the video: Kalganova begins with her weight on her right foot. She then sweeps her left leg counterclockwise to cross behind her right leg twice, moving at the rate of a quarter note each time. In the next measure, she takes two quarter-note steps forward (left-right) before bringing her left heel forward to touch her right in the last eighth of that measure. She then takes two eighth-note steps backwards (left-right). In the last measure-and-a half, she repeats the previous three-beat sequence of steps, although with some changes in orientation on the dance floor. Interestingly, these three-beat units form a grouping dissonance with the two-beat units of the music’s 2/4 meter; however, they might be said to be subtly musically motivated as well. As noted on the musical staves beneath the dance transcription, the bass line heard in this recorded performance does not use the habanera rhythm, opting instead for straight eighth-note arpeggiations, and featuring a similar internal pattern repetition that also suggests three-beat groupings. The resulting dance pattern—2+3+3—is a reversal of the 332, another common tango musical pattern that is closely related to the habanera. Please rewatch the opening of this performance, taking note of these dance-music rhythmic interactions. The video will first play the passage in slow motion without sound to give you time to connect the transcription and analysis to the video, and will then proceed with the passage a second time at speed and with music.

Conclusion

While there are many more observations that could be made about this performance using choreomusical transcription and analysis, in closing, I would like to briefly reflect on how theory and analysis provide two interrelated perspectives on dance-music investigations. As a dance-music theorist, I am trained to look for broad and somewhat universal patterns and trends, distilling diverse performances down into their essential characteristics in order to define what makes a genre or a style what it is. But as a dance-music analyst, I am also hyperfocused on the details of each individual performance. I make note of and indeed, celebrate those moments that are especially unique and unusual, those moments that do not fit the established mould and are therefore surprising and exciting. I hope to have shown both perspectives through this brief analysis of an exceptionally engaging performance of “El choclo.”