The Creation of the New Tango: The Ghosts of Ginastera, Mulligan, and Salgán in Astor Piazzolla's Musical Brainstorming

Introduction: tango in the first place

After a lifetime of arguments with his colleagues in the field of tango music, Piazzolla attended a meeting in Buenos Aires in 1988 where he met many tango musicians. There was always a discussion about whether Piazzolla’s music was tango or not. The relationship with them had been manyfold. He had worked with some and shared the tango music scene with others. Pugliese and Eladia Blazquez had always been close to Astor; Piazzolla had sometimes been disrespectful to Salgan; and he had almost had a fistfight with Vidal. It had to be a meeting of general reconciliation. In this meeting, Horacio Salgán was afraid that Astor would take the opportunity to provoke him. But he did not. On the contrary, Piazzolla expressed some warm words; he said: “Today I realize the stupidity of having quarreled for so long… How can I not be a tango man? I still remember when I played with Troilo. And when I listened to the things Horacio Salgán did, I thought: When will I be able to do something like that!” Salgán was impressed and the meeting was very moving for everyone.[1]

The quote emphasizes that, although Piazzolla often criticized his colleagues and disapproved of certain traditional tango orchestras, his deep connection to the entire tango tradition was undeniable—he knew all its styles and secrets.

Although tango was at the heart of Piazzolla’s music, he incorporated techniques and concepts from other genres, such as jazz, and from other fields such as art music. However, he never wanted his music to sound like jazz or anything else outside tango.

Astor was very creative in the way he incorporated elements of art music, through Alberto Ginastera, jazz, at different times, but very significantly through some listening to Gerry Mulligan’s arrangements of the 1950s, and some of his tango contemporaries, especially Horacio Salgán. In this paper I will try to show the process of creative reception of Ginastera, Mulligan and Salgán in Astor Piazzolla’s poiesis during the fifties.

His masters: Aníbal Troilo and Alberto Ginastera

Piazzolla joined Anibal Troilo’s orchestra in 1939 and stayed with him until mid-1943. With Troilo he learned all the secrets of tango music.[2]

In 1940 he began taking private lessons with the composer Alberto Ginastera. The studies were systematic and comprehensive and continued until Ginastera travelled to the United States at the end of 1945. Following Ginastera’s advice, Piazzolla composed art music, premiered his works and won several prizes, while also working as a tango musician, arranger and composer. In the field of art music, he adopted modernism and a neoclassical style. The first art music composition in which he incorporated tango elements into his neoclassical art music was Tanguano in 1949, and from then on, he always incorporated tango into his art music works in a structural way.[3]

He also began to use some procedures of art music to write tango music, such as the fugatti. The first time he wrote a tango fugue was in 1946, in a composition for his orquesta típica: the tango Juan Sebastián Arolas. From then on, fugatti would be a constant feature of his work, some of them as bravura pieces to close his recitals.

Piazzolla also translated his reading of Stravinsky in some rhythmic aspects and in the use of octatonic scales. We can see these elements in some works like Tango Ballet.

But he did not only transferred techniques from art music to tango music but also his understanding of neoclassicism. We can see this in twenty of his tango compositions written between 1951 and 1957, undoubtedly influenced by his activity as an academic composer. For this reason, I have proposed the term “modernist tangos” for this series of compositions, in which, as we will see, we often find the use of dissonant sonorities, and elaborated melodic features, harmonic interest, serious character and even intense expressiveness.

Main tango influences

Besides Troilo, the most important influences for Piazzola were the contemporary orchestras of Osvaldo Pugliese and Horacio Salgán. However, Troilo was his first influence. The sound of his bandoneon and some nuances in his phrasing definitely come from Troilo. As an example, we can listen to Piazzolla’s solo in La cumparsita.

But Piazzolla was very attentive to innovations in tango music, especially those introduced by Pugliese and Salgán. From Pugliese he took the strong decarean style and some compositional ideas, such as working with a repeated motif, as in the tangos La yumba or Negracha. In fact, Piazzolla recorded Negracha in 1956, which seems to be an acknowledgement of this influence.

Salgán versus Piazzolla

From Salgán, whose influence I consider to be fundamental, he took some small details.

They shared the same musical scene as directors. Salgán organized his first orchestra in 1944 and kept it until 1947, when he disbanded it. In those years Salgán performed in important places but his orchestra was considered too strange and “uncomfortable” by the tango dancers. It sounds wonderful to us today, as Piazzolla surely thought, but was not easy to understand for the traditional audience. The melodies were fragmented and divided into different voices. There were too many layers and the accompaniment was also very complex.

On his part, Piazzolla began conducting and arranging for an orchestra in 1943, when he left Troilo, and then continued until 1948.

Years later Piazzolla said that at that time only Salgán and himself were trying to innovate. Regarding Salgán, he said, “Horacio played some things better than I did, and that forced me to improve”.[4]

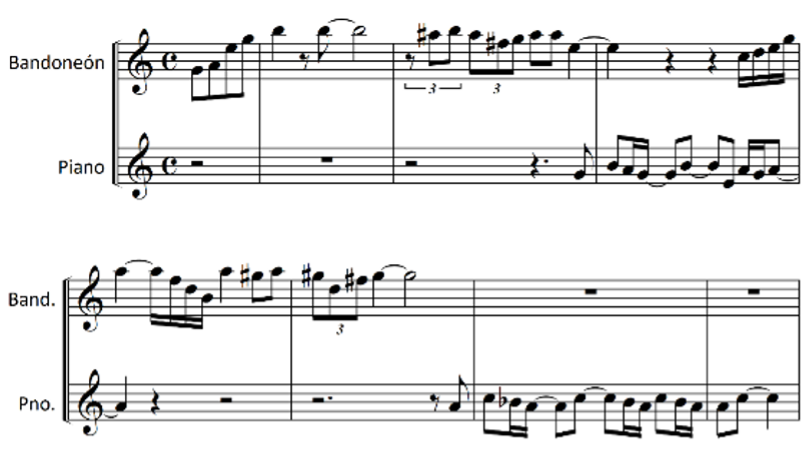

We can compare the two orchestras and point out the differences between them.

I will resort here to the description of the style of Salgán’s arrangements made by Kristine Wendland and Kacey Link.[5]

In Salgán’s arranging style, the instruments fluidly change roles between melodic and accompaniment styles. Emphasizing the melody was his primary arranging concern. He never neglected the leitmotif of the work, which had to be identifiable. Salgán’s predominant contrapuntal texture also reflected his mastery of multiple melodic lines. Quick changes in orchestration, both between and within phrases, also contributed to Salgán’s cool and airy sound.

Piazzolla’s arrangements, on the other hand, had an unstoppable drive with great rhythmic continuity and were centered on the bandoneon line. He used complex counterpoints and off-beats that interfered with the regular dance beat, a great variety of rhythmic accompaniment formulas, and frequent use of the additive 332 rhythm. He was not interested in respecting the leitmotivs of the tangos, often modifying them in rhythm and pitch.

In my opinion, in those years Salgán’s orchestra was much more modern and sophisticated than Piazzolla’s. Piazzolla surely knew this and that is why he once said: “when will I be able to write something like that?” We can compare both orchestras playing the same tango composition, Tierra querida.

Piazzolla left tango

But before Piazzolla was able to achieve something with the orquesta típica that was on a par with that of Salgán, he left the world of the tango. Piazzolla disbanded his orchestra and devoted himself to composing a lot of art music. He only remained connected to tango as a composer and arranger of a few tangos, an activity with which he obtained economic resources to live. From 1950 to 1954 he wrote five important tangos for other orchestras to record. These first compositions are what I call modernist tangos.

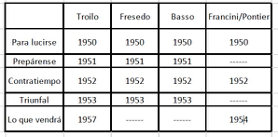

Piazzolla sold the arrangements to each orchestra of these mainstream directors: Aníbal Troilo, Osvaldo Fresedo, José Basso and Francini/Pontier. Each of them made their own recordings, thus generating a lot of rights for Piazzolla.

Many of the elements that Piazzolla used in these tangos, in melody, scales, rhythm and harmony, came from the tools used for his neoclassical language in the field of art music. The singable melodies have an irregular structure. He elaborates novel motifs for the rhythmic sections. He develops a less predictable harmonic pace than the canonical tango. All these characteristics gave a very distinctive profile to these modernist tangos.

For example, section B of Para Lucirse consists of a melodic development that defies the usual division into four-bar phrases. The melody Piazzolla wrote does not begin with a simple, singable motif. It is a serious, concentrated, intellectual tango. The resources of tango interpretation are in the ad hoc arrangements for each orchestra. We will listen to the version written for the Osvaldo Fresedo Orchestra. [Audio]

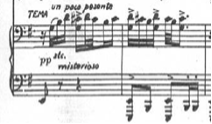

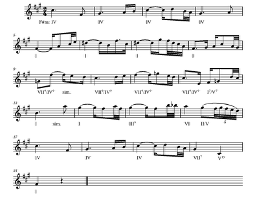

But the most interesting thing about these tangos is that in the last one, Lo que vendrá, there is a surprising influence of Salgán. For the first section, Piazzolla writes a rhythmic motif with a structure that he would use many times later.

It has a three-part structure: an upbeat beginning with a rest, a central body of rhythmic character and narrow melody, and the last part, which is what I call the Rhythmic Contraction of New Tango (RCNT). This contraction shortens the initial 2 values to prolong the last, creating a syncopation.

This RCNT is very important, because it is one of the foundations on which Piazzolla will systematically build the melodic structure of his New Tango in the 1960s.[6]

Salgán’s influence is evident here, as this motif is clearly derived from the structure of the motif from A fuego lento, the revolutionary composition by Horacio Salgán.

Let listen the two motives by Troilo’s orchestra:

Salgán would not use this type of motif in another composition. But Piazzolla will use it immediately several more times, as in Nonino, Adiós Nonino and Melancólico Buenos Aires:

Nonino

Adios Nonino

Melancólico Buenos Aires

And the most important thing is that the RCNT contained in the motif, as we will show, begins to appear frequently as a prominent element in the construction of Piazzolla’s melodies. Hence, this influence of Salgán, which at first glance was only a detail, became an aspect of great importance in the composition of the new tango.

***

We will now see something else that Piazzolla took from Salgán. It is, again, a small detail that appears in the 1957 recording of La última curda. In this wonderful arrangement Salgán uses a fill after the verse “buscando en un licor que aturda”, during which he adds a bar to generate tension before continuing on to the end.

Apparently, it was the only time Salgán used this kind of fill, but evidently Piazzolla heard it and incorporated it into his writing, because, as we will see, this type of fill is one of the tools he will use when he designs the jazz-tango in New York.

Gerry Mulligan

In 1954, Piazzolla traveled to Paris to take lessons from the renowned Nadia Boulanger. In Paris, Piazzolla listened to a lot of jazz records and visited the interesting Parisian jazz scene. He was struck by the performance of the jazz musicians, how they enjoyed playing, the individual joy of improvisation and the group enthusiasm. Piazzolla found a big difference between this jazz performance and the performance regime of the tango musicians in the cabarets of Buenos Aires, too repetitive and extensive, with tired and bored musicians. The example of the jazzmen made him think of creating an equivalent tango music that would allow him to reformulate the tango and also think of changing the places where it was played, taking the tango out of the cabaret and into the concert hall or the café concert.

Piazzolla had listened to Gerry Mulligan records (his ten-piece band and his piano-less quartet), as well as the arrangements for Birth of the Cool. And also some Stan Kenton records.

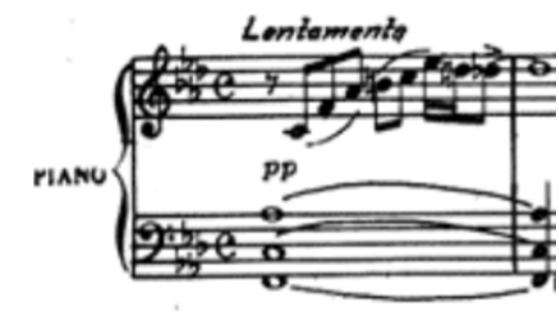

Eventually, with all this jazz listening and art music writing in mind, Piazzolla returned to tango performance, which he had abandoned in 1948. Towards the end of his stay in Paris, Piazzolla recorded sixteen tangos with solo bandoneon and string orchestra. This type of grouping was a complete novelty in the world of tango. There is some new jazz influence in them. But they are also modernist tangos, because they have features that are consistent with the tangos he had composed recently in Buenos Aires. So, the basis of these arrangements is tango with some jazz influence, and the mastery of the writing is that of an art music composer. We can listen to a fragment of Chau Paris.

The jazz influence in some of these recordings can be heard, for example, in the bandoneon solo of Prepárense, which resembles a jazz saxophone solo of the time with its discontinuous, successive ideas.

With these Parisian recordings, Piazzolla makes a brilliant return to the tango genre as a great arranger, composer and bandoneón player. For the first time, he found his own place in the tango, far beyond the possibilities of the typical orchestra. He must have felt at that moment that he was doing something equivalent to his colleague Horacio Salgán, whom he would soon surpass.

Buenos Aires again: Octeto Buenos Aires and String Orchestra

Piazzolla returns to Buenos Aires in 1955 and organizes two parallel projects: the Octeto Buenos Aires, which included an electric guitar, played by a jazz musician, although with the indication that the improvisations were not jazz; and a string orchestra with solo bandoneon, like the one in Paris. In both of them we can still hear the influence of jazz and the concept of arrangement in the manner of Gerry Mulligan or Stan Kenton. That is: fully written scores with only a little room for improvisation. The concept, but not the kind of music.

Both the arrangements for octet and for the string orchestra are much more innovative and original than Salgán’s. They truly mark the beginning of a new era in tango.

But evidently Piazzolla had not yet managed to overcome the state of competition with Salgán. With the Octeto Buenos Aires he recorded A fuego lento, the composition that had so much influence on Piazzolla. And he also wrote arrangements of Mi refugio, Los mareados, Boedo and El Marne, all of them tangos that Salgán had previously recorded with his orquesta típica. It is as if Piazzolla wanted to somehow settle his rivalry with Salgán with these versions, to show that he could surpass him.

With the two ensembles he recorded 42 tangos between 1956 and 1957 in which all the influences are already present: the ghosts of Stravinski, Mulligan and Ginastera intertwine in a tango embrace with Troilo, Salgán and Pugliese in the complex poiesis developed with genius by Piazzolla.

With the Octeto Buenos Aires, Piazzolla tried to make his mark in the history of the tango by breaking through as an avant-garde. He even published an artistic manifesto. The repertoire he chose consisted almost entirely of classical tangos, which he reformulated until they were almost unrecognizable.

The string orchestra repertory included more compositional experimentation. Stravinsky influences are recognized as well as the use of the motif with the RCNT.

New York: jazz + (again) Salgán

After the commercial failure of the Octeto and the String Orchestra in Buenos Aires, Piazzolla decided to emigrate to the United States. He left in February 1958. Once in New York, he found a way to enter the music world and finally he was hired by the Roulette label as an arranger. He worked on nine albums. The last two albums were the famous Jazz-Tango works.

He explained to his friends that jazz tango was an attempt to capture the American public, whose ears were not accustomed to real tango, but who could be captivated by familiar melodies played in tango rhythm.

The famous LP in which he incorporates the jazz-tango concept is “Take me dancing. The Latin Rhythms of Astor Piazzolla & his Quintet”. It includes eight compositions by Piazzolla and four classics of American popular music.

On the back cover we read

Today Piazzolla is the foremost exponent of the [bandoneón] and in this album he ably presents his theory of mixing the jazz beat with the tango and other Latin-American rhythms. Piazzolla calls this rhythm “Jazz-Tango” and it is this rhythm that is the essence of this album.

Piazzolla transforms the melodies of the tangos to adapt them to the rhythmic performance of jazz and proposes the insertion of tango in the performance of jazz classics. It is not a juxtaposition, but a true fusion, because there is a structural combination of musical elements.

In Laura the bandoneon plays like a jazz improvisation and the accompaniment is written and played by the piano, guitar and vibes, so it doesn’t work in the jazz way where the rhythm group develops the accompaniment in an improvised way. They obviously follow strictly written parts. Piazzolla wrote fills (similar to the Salgán model) which included the RCNT. [Audio]

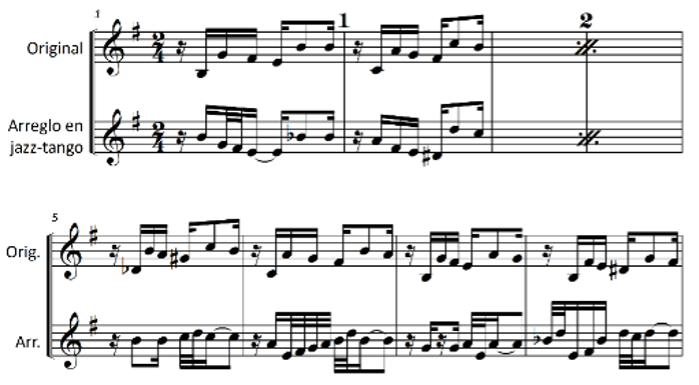

On the other side in his tango Triunfal he modifies the rhythm of the melody, introducing the syncopation produced by the RCNT in the first four measures. In the next four measures he modified the motive and gives it swing by also applying the RCNT. We will listen the classical version and then the Jazz_Tango version. AUDIO / AUDIO

The last measures of section A are written over a descending reiteration, with a melancholic effect. Piazzolla cuts this effect with an ending based on a descending chromatic scale, with a neutral effect and a neutral end. We can see the difference between Troilo’s dramatic and melancholic version, according to the original composition, and the jazz-tango arrangement.

Welcome Mr. Piazzolla

Piazzolla returned to Buenos Aires in 1960. Almost immediately, Nuevo Tango began to take shape as the final product of all the previous activities we have seen.

One of Astor Piazzolla’s first engagements was his starring role in a television show: Welcome Mr. Piazzolla (the title was in English). The sound of the broadcast of 15.8.1960 has been preserved in a direct recording from the speaker of a small television set. The sound is not good, but it gives us a glimpse of the script of the show and the repertoire that Piazzolla played in it.

Astor humorously recounted that in New York they didn’t know the bandoneon, and that the record company executive had asked him to include castanets in the arrangements, and that they said he didn’t do real tango. The script is also full of exaggerations and inaccuracies.

The most important is the repertoire he played on that programme: his modernist tangos, such as Tres minutos con la realidad, and also the version of Laura recorded on the Jazz Tango disc. It was on this basis that he began the Nuevo Tango, applying the fills and the RCNT that he used so systematically in the Jazz Tango.

We can see how this practice continued, for example, in a 1961 arrangement of the tango Garúa, in which he uses the same fill from the 1958 arrangement of Derecho viejo in NY.

The Nuevo Tango was the result of a long brainstorming, a complex poiesis in which Piazzolla used his knowledge of art music, but incorporated structural aspects of Salgán and the swing of jazz. He brought his new ideas from Europe or the United States, but anchored them firmly in his tango tradition.

[1] Azzi. María Susana and Simon Collier: Le Grand Tango. The Life and Music of Astor Piazzolla (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 257-258.

[2] García Brunelli, Omar: La música de Astor Piazzolla (Buenos Aires: Gourmet Musical, 2022).

[3] Ibidem.

[4] Sperati, Alberto. Con Piazzolla (Buenos Aires: Garlerna, 1969).

[5] Link, Kacey y Kristin Wendland: Tracing tangueros. Argentine tango instrumental Music (New York:

Oxford University Press, 2016).

[6] I have to thank Martin Kutnowski, who first pointed out the structural feature of this motif in an article published in the Latin American Music Review in 2002.